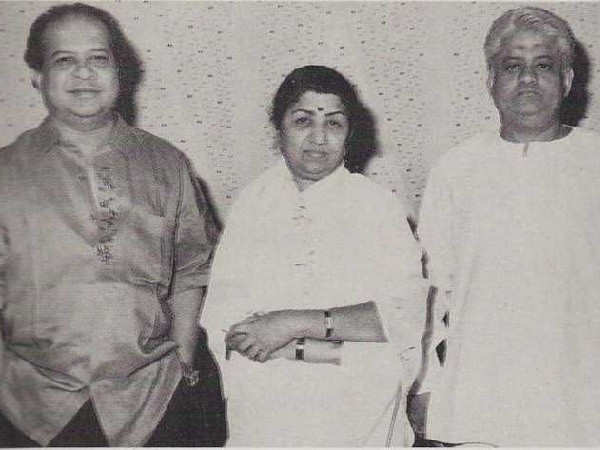

Few have the privilege of spending their formative years with Lata Mangeshkar. Of the joy of eating food cooked out of her hands. Waking up to her morning ragas along with the choir of the birds. Or even being gifted an idol of Lord Shiva. But Pyarelal of the famed composer duo Laxmikant-Pyarelal did. An association, which began when he was just a boy bowing the violin to survive, went on to create a musical legacy. Pyarelal Sharma and his friend and partner, the late Laxmikant Shantaram Kudalkar, have the distinction of having Lata Mangeshkar sing the most songs for them. If Chalo sajna jahan tak ghata chale (Mere Humdam Mere Dost, 1969) with a sumptuous use of santoor and dholak along with Western instruments, is wistful and beckoning, Suno sajna papihe ne kaha sabse (Aaye Din Bahar Ke,1966), based on raag pahadi, heralds the song and sensuality of spring. If they convinced Lata to sing the delicate cabaret number Aa jaane jaa (Inteqam, 1968), inspired by Arabic singer Fayrooz, replete with ‘nakhra’ and ‘harkat’, they sound-tracked her at her spiritual best in the title song of Satyam Shivam Sundaram… In more than 700 songs with India’s Nightingale, Lata’s voice was a catalyst for the concertmasters. “We’ve been blessed by Saraswati Maa and Lata Maa. Every time I met Didi (Lata), I wouldn’t just touch her feet; I’d place my head on them.” Pointing towards the mandir, where Shiva’s idol, Lata’s souvenir to him, holds pride of place, Pyarelal says, “Didi is devi ka aashirwad for us!”

DESTINY & DIDI

In the late 40s, Pyarelal Sharma, barely eight, played the violin in music shows and recordings in a bid to survive. “My father (Ram Prasan Sharma, who played the trumpet in the military and police bands of Baroda), taught me western music,” beams Pyarelal, who was called ‘Pyaare’ by his mother. “In Mumbai, we lived in a one-room kitchen apartment in Prabhadevi. I’d wake up at 5 a.m. to wash my only pair of clothes and hang them out to dry. Then around 9 a.m., I’d iron those clothes and put them on, even if they were a bit moist,” shares Pyarelal of his early struggle. Laxmikant Shantaram Kudalkar, in his early teens, played the mandolin on recordings. One day, he befriended Pyarelal, who was playing cricket outside Famous Studios. The two then joined Hridaynath Mangeshkar’s Sureela Bal Kala Kendra and began performing in shows. The boys would hang out at singer Lata Mangeshkar’s three-bedroom hall apartment in Walkeshwar. “Bala saab (Hridaynath) had composed a Marathi song, Tinhi aanja sakhe... I arranged the music at the age of 11. Lata Didi sang it,” he recalls of his first ‘collaboration’ with her. “On Sundays, Didi would cook mutton and fish... Our job was to praise her.

She spoke little but was always kind to us. She’d go abroad twice a year. I had so much haq (right) that in her absence, I’d get to sleep on her bed,” he smiles. On Lata’s commendation, teenagers Laxmikant and Pyarelal began playing for top composers, including Naushad, Madan Mohan, and Shankar-Jaikishen. “Our lunch budget was 5 annas per person. I was badtameez and would want to eat whatever I fancied. But Laxmiji would insist that we budget it—two wadas for two annas, one missal for two annas and two pavs for one anna,” he says of his dear friend. In 1963, Babubhai Mistry Parasmani gave birth to the composing team of Laxmikant-Pyarelal (L-P). “Naushad Saab used to have 20 violins and Shankar-Jaikishan 30 in the orchestra. We used 36!” beams Pyarelal. Hansta hua noorani chehra, Roshan tumhi se duniya, Chori chori jo tumse mili, Woh jab yaad aaye and Ui maa ui maa... All were chartbusters

DOSTI WITH FILMFARE

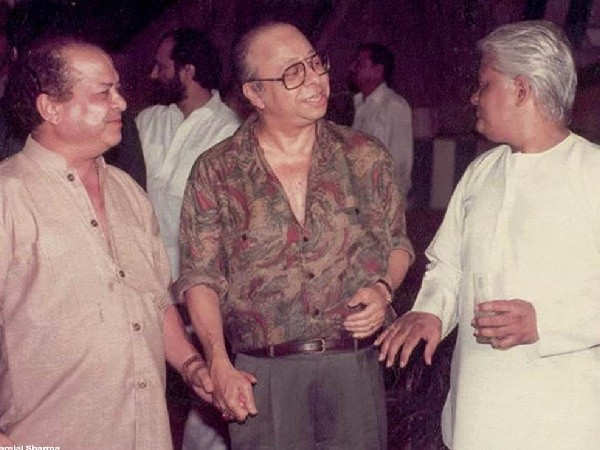

But Parasmani didn’t change their fortunes immediately. “After we became composers, we were not called for recordings by other composers. They feared we’d copy their tunes. We had become so broke that Laxmiji and I would drink Rs 10 wala cheap liquor with names like Mosambi, Peru, and Santra,” he laughs. It was Rajshri Productions’ Dosti (1964) that befriended them with fortune. It was a black-andwhite film about two friends, one visually challenged and the other physically impaired. It had no commercial trappings. “That year, films including Raj Kapoor’s Sangam and Woh Kaun Thi? (I’d even played the violin for Madan Mohan) had great music. We knew we’d never get the Filmfare Award, but just making it to the nomination list meant a lot for us,” says Pyarelal. One morning, Pyarelal was woken up abruptly when he heard a loud voice say, ‘Gadhero uth! (Wake up, you donkey!). You’ve won the Filmfare Award!’ “It was Anna Saab (C. Ramchandra). He had given us work when we had nothing. He was the one to give us the good news as well. We rushed to Didi to share this news. Laxmiji and I got suits stitched for the occasion.” 1967 was a significant year for L-P, with the hit scores of Shagird, Milan, Farz, Patthar Ke Sanam, and Anita sung by Lata. This was followed by chartbusters in Humjoli, Roti Kapda Aur Makaan, Amar Akbar Anthony, Sargam, etc. in the ’70s. But nothing came close to the banger that Raj Kapoor’s Bobby (1973) was.

RAJ KAPOOR’S BOBBY

Raj Kapoor, who only worked with Shankar-Jaikishan, sent word to L-P through singer Mukesh, asking them to compose for Bobby (1973). But L-P were reluctant to accept the film after Jaikishen had passed away in 1972 and Shankar was alone. They had idolised Shankar Jaikishen all along. “We’d follow them around. At 11 a.m., Jaikishenji would be sitting in a music hall. Then he’d have lunch at a hotel. In the evening, he’d compose songs in another hotel,” says Pyarelal, adding, “Jaikishenji was handsome. Laxmiji would copy his upturned collar style and wear the watch on his right wrist like him. Jaikishenji gifted me a silver violin on my birthday.” L-P eventually agreed to compose for Raj Kapoor because if not for them, someone else would have done the film. Pyarelal recalls his first meeting with Raj Kapoor. “Raj Saab stirred the sugar in his tea with an ulta spoon anti-clockwise twice around. He smoked only 555 cigarettes. He opened the carton in a stylish way so that the cigarette popped up. He picked it from his mouth and placed the cigarette between his fingers in an unusual way.” While Shailendra Singh was chosen as the voice of the young Rishi Kapoor, Lata sang for Dimple Kapadia. “Didi, Raj Saab’s favourite, had stopped singing for him for some time (allegedly on the issue of royalty). We facilitated their patch-up. Jhoot bole kauwa kate was the first song Didi recorded,” he maintains. “Didi’s Ankhiyon ko rehne de was based on Reshmaji’s Punjabi thumri, Ankhiyon noon rehan de.” After Bobby, L-P composed the music for RK’s Satyam Shivam Sundaram (1978) and Prem Rog (1982). “For the title song of Satyam... There were around 180 musicians: 60 in the chorus, 28 rhythm players and six assistants conducting the session. The rhythm players, playing before Didi, didn’t have a conductor. She stepped in, saying, “Thamb thamb (wait)!” She held her diary in one hand and instructed the rhythm players with the other,” he smiles. Raj Saab would often visit Pyarelal’s sea-facing house or Laxmikant’s house for drinks. “Laxmiji and I had one bottle of Black & White, each costing Rs 1200, those days. Raj Saab would have Chivas Regal. We spent around Rs. 3000 on alcohol every day. Once Raj Saab reached Laxmi’s home at 3 p.m. and blew the horn. Laxmi was asleep, and Raj Saab had to return. Raj Saab was upset. Though Laxmi and Raj Saab did become friends again, we never worked together again.”

GRACIOUS DIDI

Pyarelal recalls his infamous spat with Laxmikant during a show in Dubai. “I was thirsty. I asked Laxmiji to send me water, which never came. After some time, when I got off the stage, I saw Laxmiji with six bottles of water and two bottles of whisky. He was merrily drinking. I was miffed and decided not to work with him. Back home, we had several recordings lined up. So Laxmiji sent me a telegram asking me to come. I didn’t.” Filmmakers J. Om Prakashji and Subhash Ghai got the duo together. “They made us garland each other at Mehboob Studio before we recorded a song. Didi said, “Apni baatein apne mein rakho, bahar mat jaane do (keep your issues between yourselves; don’t make them public)!” Pyarelal recalls the moment when Lata, who had consecutively won the Filmfare Award for more than a decade, decided to make way for other talent. “Didi was performing for the Filmfare Awards in 1970. After singing Achcha toh hum chalte hain (Aan Milo Sajna, 1970), she picked up her purse hanging on the mike, said ‘Ta ta’ to the audience, aur purse hilate huye chali gayee. While receiving the award the same evening (for Jeene Ki Raah), she announced that this would be her last.” DIDI – THE PERSON Pyarelal recalls Lata’s affectionate nature. “Didi was extremely fond of Pakistani singer Noorjehan. They met twice a year on the border. They’d carry meals lovingly prepared for each other. They’d sit and chat for a few hours.” Lata was equally close to the late thespian Dilip Kumar. “It was Dilip Saab who urged her to get the Urdu accent right. She worked on it for three years. She’d write every song in her diary. She’d mark the harkats on it.

For instance, the song Bindiya chamkegi (Do Raaste,1969) is full of harkats. But before every intonation, she’d ask, ‘Yeh harkat theek hai na?’” says Pyarelal adding, “She never ate before a recording.” Her quiet, unassuming aura was unmistakable. “She always wore white. The minute she came in, we’d know. There would be a murmur. I could sense her khusboo.” Given Pyarelal’s strong grounding in Western music, Lata once happened to remark, “Pyare tum symphony kyun nahi likhte ho?” Soon, he wrote the symphonies Om Shivam (in A Minor) and Concert #2 (in D Minor). “It’s about Lord Shiva visiting Germany and what he saw once he set foot outside.” While the world applauded him, the finest compliment came from Lata. “One day Didi called and asked, ‘Has someone come to you?’ Just then, the bell rang. I went across to open the door, with Didi still on the line with me. There was a man holding Shivji’s murti. Didi had sent it to me as a mark of appreciation.” Continuing in the emotional vein, he adds, “Around 25 days before she passed away, she spoke to me for an hour. In fact, she’d called up all those who were close to her. Maybe she had a premonition.

She left a priceless piece of advice. She said, ‘Dekho Pyaare, dosti karna hai toh dushman se karo!’ The words keep ringing in my ears.”

SHOW COMMENTS