While some say Chamak is directly inspired by the lives of Amar Singh Chamkila and Sidhu Moosewala, who were killed in 1988 and 2022, respectively, the director says it’s not the case. “Only now do we get to hear about Sidhu Moosewala, Amar Singh Chamkila, there have been many artistes in Punjab like this, who have given up their lives for the sake of art.” Bizarrely, a week before the release of the series, Punjabi singer and actor Gippy Grewal, who plays the role of Taara Singh, was targeted in an attack on his house in Canada. Gunmen fired shots outside the property, and gangster Lawrence Bishnoi, an accused in the Sidhu Moosewala murder case and an associate of Goldy Brar, reportedly took credit. The director himself has received threats for exposing the dark underbelly of Punjabi music, but he stands true to his beliefs. “I am not exposing anyone; I am just revealing the real face of the industry. Behind the bling, there is so much darkness, and with the passion, there is so much crime and jealousy. I never want an artiste to be killed. An artiste should never be killed,” he states. The director reveals he had approached Moosewala for a guest appearance in Chamak. “I had approached him to play a cameo.I spoke to him over the phone, and he said,’Paaji, we will work together for sure’. But it wasn’t to be. He was killed before I could film the segment with him.”

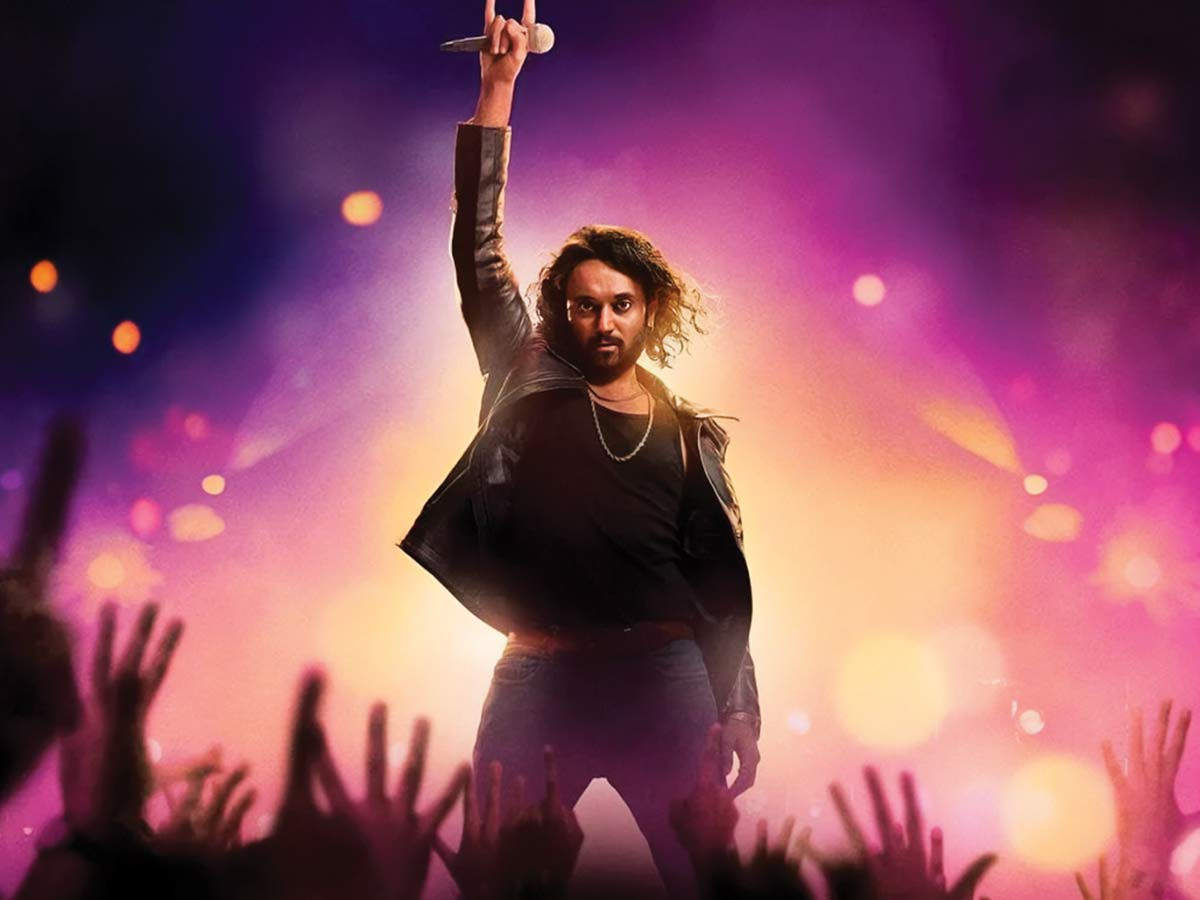

Incidentally, his series, which is called Chamak, which means shine, literally states the fact that all that shines may not be gold. “If you notice, my protagonist’s name in the series is Kaala, signifying that there is darkness within every bright thing. These are the little things that I’ve added, which say it all.” The series is said to have shock value, but the director says the violence shown in the series isn’t just to titillate but to show that we do live in violent times. He yearns for simpler times but adds that violence has always been part of Punjab. “Look at what happened to Punjab during Partition. Brother killed brother for no reason at all. One of the most flourishing regions in the world got divided. And we’re still dealing with the repercussions of it. When the echoes of Partition had somewhat died down, violence raised its ugly head once more during the ’80s during the militancy days. Then, Punjab had to deal with a wide-spread drug problem. There has been no respite for its people and yet they make such good music.”

The director says that while on one hand, everyone knows everyone in the Punjabi music industry and people may maintain a facade of solidarity, the true picture is something else indeed. He states that singers have been known to use underhand tactics in some cases to get the best dates and venues. There is big money in stage shows and not getting good venues may lead to a slump. He points out that the artistes are an insecure breed, despite all their popularity, or perhaps because of it. He shakes his head and says that the rivalries may not be fathomed by an outsider but they definitely exist. He cites the reasons for that. “After Bollywood music, the Punjabi music industry is the biggest music industry in India, with a global following,” he expounds. “Some say its reach is bigger than that of Bollywood. That has led to some strange kinds of rivalries. These artistes are superstars in their own right. They zoom around in the latest cars, wear the costliest labels and the trendiest sneakers, and have homes in multiple countries. And are always playing a game of one-upmanship with each other,” he bemoans. “Sometimes, the competition goes too far. I’ve heard of instances where someone has blocked the other person from reaching his venue on time. It may look juvenile, but it happens.”

He gives the example of a rapper who used to say he’s a Rolls Royce while everyone else is a Nano and then he even brought a Rolls Royce for himself. The director rues the fact that while earlier, the lyrics in Punjabi songs were spiritual in nature and targeted the wrongs of society or asked the people to live in harmony, today’s songs are mostly about material things, or worse, promote gun and drug culture. “There are artistes, like the legendary Gurdas Mann, who’ve always chosen lyrics that are meaningful. And that has led to their long shelf life. But today’s lyrics are all full of names of sports cars; they revolve around impressing girls and if you go deeper, hint at drugs and guns. They may be popular, but they paint an unsavoury picture of Punjab.”

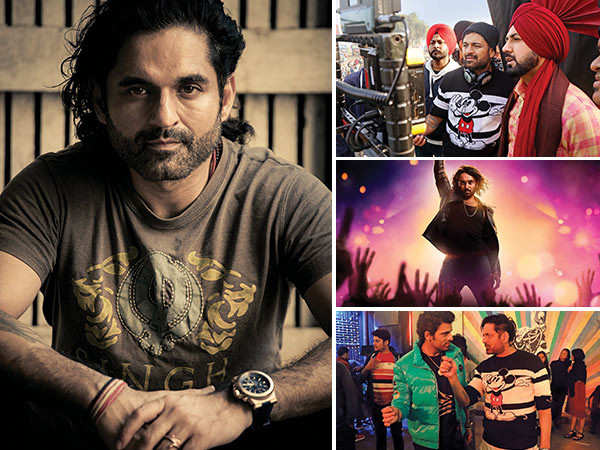

Chamak isn’t Rohit Jugraj’s first rodeo. He has assisted directors like Sanjay Leela Bhansali and Ram Gopal Verma in the past, and he says the time he has spent with such stalwarts helped him become who he is today. He doesn’t get drawn into the outsider versus insider debate, saying that everyone has their own struggle. “Ranbir Kapoor was Bhansali sir’s assistant along with me. Yes, he used to come on the sets in a luxury car, and I used to come in a rickshaw back then. But we used to do the same grunt work on the sets. He wasn’t favoured just because he belonged to the Kapoor family. You won’t understand the kind of pressure the star kids face. Yes, they may have everything on the surface, but it takes one false note in front of the camera for it all to go away. They have a reputation to maintain, and they know that they can’t afford to goof up. I had my own set of struggles, like how to pay the rent or my other bills on time; they didn’t have to face that, but there was less pressure on my head than what they bore.”

Rohit started out with movies like James (2005) and Superstar (2008), which, however, didn’t work at the box office. He shifted his bag and baggage to the Punjabi industry, which welcomed him with open arms. His first Punjabi film, Jatt James Bond (2014), was a heist comedy and starred Gippy Grewal. His second, Sardaar Ji (2015), was a horror comedy and starred Diljit Dosanjh. The film’s tremendous success led to a sequel, Sardaar Ji 2 (2016), which too raked in the moolah. After having proved his mettle, he came back to an all-India landscape as a changed man. “The Punjabi industry gave me everything; I’d forever be grateful to it for that. And I haven’t cut off ties with it. My production house, RG Rudram Productions, is in the process of greenlighting Punjabi content as well.” While R in the production house’s title stands for his own name, G stands for Geetanjali Mehlwal Chauhan, his wife and business partner, who is also one of the writers of the series. “We literally want to reach the stars. We’ve realised the global reach of the OTT, and we’re aiming for international projects and tie-ups, besides regional content. Comedy is something I want to explore more, and after the dark space that Chamak was set in, maybe I’ll try my hand at comedy.” He’s not averse to the idea of directing a feature film as well. “I’m a full-blown masala film buff. Yes, I love world cinema, and I love art cinema, but my heart belongs to commercial films. So to make a full-blown, commercial pan-Indian film has always been a dream. And thankfully, I’m in a position now to do so. But everything is in a nascent stage now, so I can’t provide more details.”

SHOW COMMENTS